How to spend New Year in Japan? It is very different from Western tradition. Of course, nowadays there are fireworks and countdown parties, like in other countries, but the tradition is a little different. New Year is a time for families to come together. Many people take a few days off to spend time with their loved ones, reflecting on the past year and looking forward to the new one. There are 5 words that represent the Japanese New Year; please take a look to understand its culture.

In 2024, it’s the Year of the Dragon. If you’re curious about the “ETO,” the animal sign, please refer to below.

Table of Contents

Quick Video Guide

Cleaning / Osoji

In Japanese New Year traditions, there is a belief in the “Toshigami-sama / 歳神様.” This deity is thought to bring new happiness to each household in the coming year. As part of the preparations to welcome this deity, there is a custom known as “Oosoji” or major cleaning of the home. Traditionally, it is encouraged to complete this thorough cleaning by December 28th. This is because December 29th, containing the number 9, can be associated with the word “ku,” meaning suffering. By finishing the cleaning well in advance, there is a sense of readiness and a fresh start as the new year begins.

Kadomatsu and Shimekazari

Once the cleaning is complete, traditional New Year decorations are put up. Decorations such as kadomatsu or shimekazari are commonly placed at the entrance of homes. Kadomatsu is typically made with auspicious materials like pine, bamboo, and plum branches, symbolizing good fortune in Japan. The kadomatsu placed at the gate or in front of the entrance serves as a marker for Toshigami-sama, the deity, as they enter the house.

Shimekazari, on the other hand, acts as a boundary between the area of the deity and our living space, playing a role in preventing impure elements from entering the house.

Lastly, the kagami-mochi is considered a temporary dwelling for the welcomed deity during the New Year.

Similar to the cleaning and decorating traditions, it is customary to avoid placing these decorations on the 29th. In Japan, the number 8 is considered auspicious, so households often decorate with these on December 28th.

Omisoka

New Year’s Eve is called Omisoka, written as 大晦日 in Kanji. On this day, you might hear the bell ringing from the temple. This is “Joya-no-Kane/ 除夜の鐘,” where the bell is rung 108 times, expressing the hope to eliminate the 108 worldly afflictions of people. The bell rings from New Year’s Eve to New Year’s Day. In temples where 108 rings are performed, it is common to ring up to 107 times on New Year’s Eve and complete the final toll after the arrival of the new year.

Additionally, on New Year’s Eve, there is a custom of eating Toshikoshi-Soba. The reasons for this vary, but one explanation is that since soba noodles are long, they symbolize an extended life. People eat Toshikoshi-Soba with the wish for longer lives and the overall happiness of the family.

Osechi

- Datemaki (Rolled sweet omelet): Symbolizing a rolled scroll, it is a wish for academic achievement.

- Kazunoko (Herring roe): With numerous eggs attached, it represents a wish for the prosperity of descendants.

- Kuromame (Sweet black beans): Wishing for good health.

- Kuri-kinton (Sweet mashed potato with chestnuts): Associated with money and luck.

Hatsumode

Hatsumode, the First Visit to a Shrine or temple, written as 初詣, is a significant tradition in Japan. While there is no specific date one must go, many people choose to visit during the first few days of the New Year to pray for good fortune and health. Some companies also participate in Hatsumode on the first business day of the year to seek blessings from the deity for business prosperity. This period often witnesses long queues at shrines and temples.

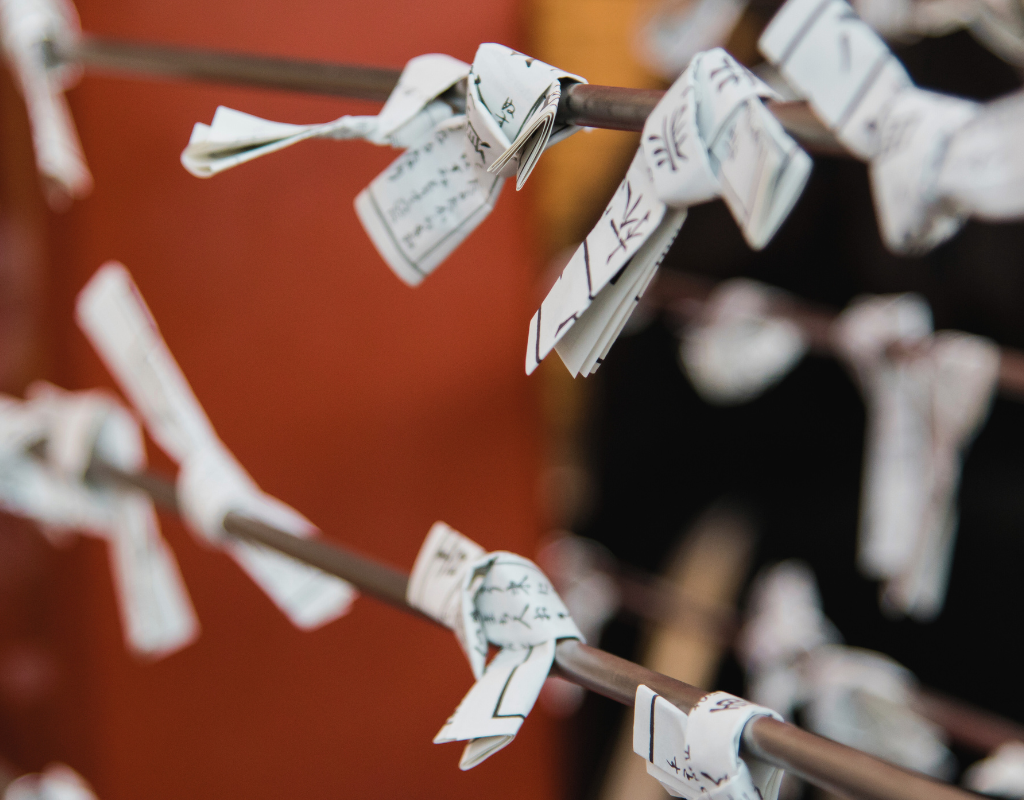

During Hatsumode, some individuals participate in Omikuji, written as おみくじ in hiragana, to discover their fortune for the year. While there are no strict rules, after drawing an Omikuji, some people tie it to a designated area on the shrine or temple, while others choose to take it home. The significance of luck varies, with “大吉” (daikichi or great fortune) considered the most fortunate, and “凶” (kyo or bad luck) seen as the lowest point in fortune, signifying that things cannot get any worse. Interestingly, the appearance of “凶” is also interpreted as a turning point where fortune can only improve, indicating a positive shift in luck.